Three cache layers between SELECT and disk

Saturday, 2 AM. We had a Postgres incident earlier that week - Heroku timeouts, queries running for 35+ minutes, IOPS hitting the provisioned limit. I should have been sleeping. Instead I was staring at EXPLAIN ANALYZE output, asking myself a question I couldn’t let go: what actually happens when Postgres reads from disk?

I knew I needed a better index. But before fixing anything, I wanted to understand what “reading from disk” actually means. How many layers of caching exist between a SELECT and the actual storage device? And what happens when they all fail?

Three layers between Postgres and disk

When Postgres decides it needs a page (8KB, the default), the data can come from three different places. Each one is a cache layer, and each one has a different cost.

Layer 1: shared buffers

Shared buffers is Postgres’ own cache. It lives in the Postgres process memory. When Postgres needs a page, it checks here first. If the page is in shared buffers, great - no system call, no kernel involvement. Just a memory read within the process.

Ours was set to 4GB, which is the default recommendation. The Postgres docs suggest 25% of total RAM, and there’s a reason for that - we’ll get to it.

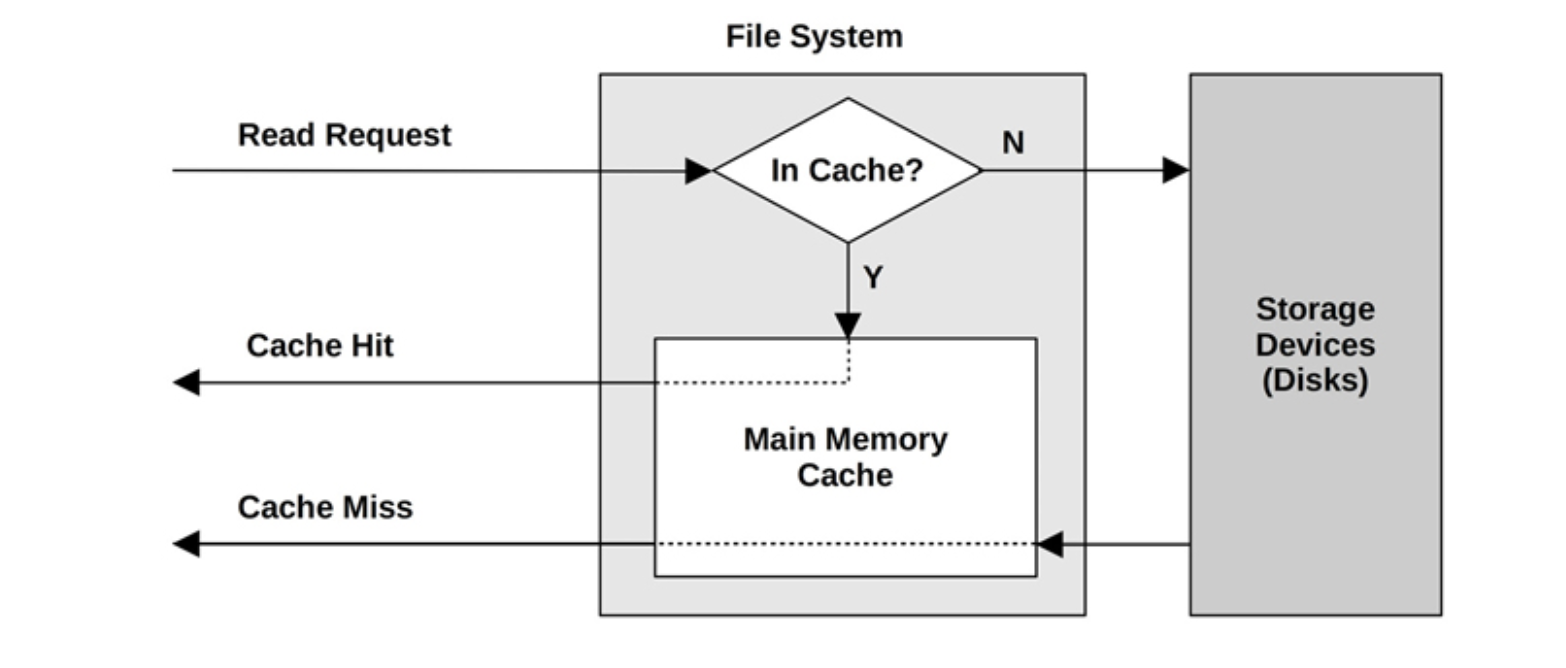

Layer 2: OS page cache

Image from Brendan Gregg’s book - System Performance

If the page is not in shared buffers, Postgres calls read(2), and now we’re in kernel territory.

The kernel maintains its own cache of disk blocks: the page cache. When Postgres asks the OS for a page, the kernel checks if that block is already cached in memory. If it is, the kernel returns it immediately. No disk I/O happened - from Postgres’ perspective it was a “shared buffer miss”, but from the OS perspective it was still a memory read.

This is why free -h on a Linux box can look alarming. You see almost no “free” memory, but most of it is “available” - and the page cache is using it. Linux fills free memory with page cache on purpose. It’s a bet: if someone reads this block again, I already have it. And if the OS needs that memory for an actual process, it just drops the cached pages. They can always be re-read from disk.

The interesting part: shared buffers and page cache compete for the same physical RAM. If you increase shared buffers from 4GB to 16GB, that’s 12GB less for page cache. Postgres might cache more pages internally, but the OS caches fewer disk blocks - and the OS page cache benefits everything, not just the pages Postgres explicitly requested. There’s a point where increasing shared buffers actually hurts performance because you’re starving the page cache.

Layer 3: disk

If the page is not in shared buffers, and not in page cache either, the kernel sends an I/O request to the device driver. In Heroku’s case, that device is AWS EBS - a network-attached block storage. This is the expensive path, and this is what counts as one IOPS.

And here’s where I hit a wall. I wanted to understand more about the physical storage - do EBS volumes have their own DRAM cache? What’s the actual latency profile? But Heroku is managed. I can’t see the hardware. I can’t run hdparm, can’t check the drive specs, can’t see if there’s a controller cache between EBS and the actual storage medium. The abstraction hides exactly the layer I wanted to understand.

What I can see is the IOPS limit: 3000 provisioned, with EBS burst credits allowing temporary spikes above that. Our logs showed reads hitting 3668 IOPS - the burst credits were keeping us alive, but once they’re gone, you’re hard-capped.

But what is Postgres actually reading?

All this talk about pages and disk reads - but what does a page actually look like? I explored this a while ago with a simple table, while doing some exercises with Oz Nova:

postgres=# create table foo (id int, age smallint, name varchar(100));

CREATE TABLE

We can find the file Postgres stores the table in with SELECT pg_relation_filepath('foo');, and then hexdump it:

root@frn:# hexdump -C 16388

00000000 00 00 00 00 60 7e 55 01 00 00 00 00 1c 00 d8 1f |....`~U.........|

00000010 00 20 04 20 00 00 00 00 d8 9f 4a 00 00 00 00 00 |. . ......J.....|

00000020 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 |................|

*

00001fd0 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 e0 02 00 00 00 00 00 00 |................|

00001fe0 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 01 00 03 00 02 08 18 00 |................|

00001ff0 01 00 00 00 13 00 0f 4d 69 63 6b 65 79 00 00 00 |.......Mickey...|

00002000

There it is. “Mickey” sitting at the bottom of the page. The file is 8192 bytes - one Postgres page - even though we only inserted one row. Each page has three things: header data at the top, line pointers (which point to each tuple), and the actual heap tuples stacked at the bottom. New tuples grow from the bottom up.

One detail that surprised me: the data wasn’t in the file until I ran CHECKPOINT. Before that, it only existed in memory. CHECKPOINT flushes everything to disk.

work_mem and the spill problem

There’s one more piece of the memory puzzle: work_mem. This is the memory Postgres allocates per operation for things like sorts, hash joins, and hash aggregations.

Ours was set to 8MB. If a sort result doesn’t fit in 8MB, Postgres creates temporary files on disk. That’s additional I/O - and those temp file reads and writes also go through the same path: kernel, page cache, maybe disk.

A small work_mem means more sorts spill to disk. A large work_mem means each query operation eats more memory - and if you have many concurrent queries, the total memory consumed can push out shared buffers or page cache. It’s all the same RAM.

The cache hit ratio

Our overall cache hit ratio was ~78%, measured at the shared buffers level:

SELECT

sum(heap_blks_read) as heap_read,

sum(heap_blks_hit) as heap_hit,

sum(heap_blks_hit)::float / nullif(sum(heap_blks_hit) + sum(heap_blks_read), 0) as ratio

FROM pg_statio_user_tables;

- 0.784

But this number is misleading if you don’t understand the layers. pg_statio_user_tables counts shared buffer hits vs shared buffer misses. A “miss” here means Postgres asked the OS for the page - but the OS might still serve it from page cache. So the 78% is the Postgres-level hit ratio, not the actual “went to disk” ratio.

The real disk read ratio is lower - some of those 22% “misses” were served from page cache without any I/O. But during the overnight schedulers, when the working set exceeded both caches, the actual disk reads spiked hard.

What was actually killing us

The table at the center of this is a large one. 46.7GB heap + TOAST, 28.1GB in indexes. Peaks of 4000 updates per minute. It stores lead data with large JSONB columns.

I found two query patterns doing most of the IOPS damage. Both follow the exact same pathology: filter by account_id using an index, then apply JSONB filters and other conditions after fetching the rows from disk.

The EXPLAIN ANALYZE

Here’s a representative sample:

Index Scan using idx_account_id on leads

Filter: ((some_column IS NULL) AND (jsonb_condition))

Index Cond: (account_id = 4939)

Rows Removed by Filter: 39811

Buffers: shared hit=10871 read=27841 dirtied=3

I/O Timings: shared/local read=13838.335

39,811 rows fetched from disk. All discarded by the filter. Zero rows returned.

Let’s do the math. 27,841 block reads × 8KB per block = ~217MB read from disk. In 14 seconds of execution. That’s ~1,989 IOPS from a single query that returned nothing.

The second pattern was similar: 12,071 rows fetched and discarded, ~107MB from disk, ~1,944 IOPS. Also zero rows returned.

Two layers of disk access

Reading from an index is also a disk read. The B-tree index itself lives on disk (or in cache, if you’re lucky). Postgres first traverses the index pages to find the row pointers, and then follows those pointers to the heap to fetch the actual rows.

So the access pattern is: read index pages → get a list of row locations → read heap pages at those locations. Two rounds of I/O. And the heap fetches are essentially random - the rows for a given account_id are scattered across the table, especially in a table with thousands of updates per minute where MVCC keeps creating new tuples in different pages. The index tells Postgres where the rows are, but “where” can mean thousands of different pages spread across a 46GB table.

The root cause

Both queries used a plain B-tree index on account_id. Nothing else.

This index says: “account 4939 has 39,811 rows, here’s where they are on disk.” But it knows nothing about the JSONB columns or other filtered fields. That information only exists in the heap.

So Postgres fetches all 39,811 rows from disk, reads them, checks the filters, and throws away everything. Hundreds of megabytes of reads for zero results. Two of these running at the same time is enough to blow past 3000 IOPS.

The fix is probably a GIN index on the JSONB column, so Postgres can evaluate those filters inside the index scan without fetching rows from the heap. A partial index for the NULL condition would also help. We haven’t deployed it yet - I wrote this on a Sunday, and the devs will look at it on Monday.

But what I actually took from this weekend is not the fix. I went into this wanting to understand how disks work, and I ended up learning more about how Postgres uses memory - the three cache layers, how they compete for RAM, and how a bad index can force Postgres through all of them for rows it’s going to throw away anyway. In a managed environment like Heroku, you can’t even see the bottom of the stack, which is frustrating. But at least now I understand the layers above it a bit better.

Postgres updates and rows scattering

Postgres doesn’t update tuples in place. When you update a row, it marks the old tuple as deleted and inserts a new one at the bottom of the page. We can see this with ctid, a pseudo-column that shows (page, offset):

postgres=# select ctid, value from test;

ctid | value

-------+-------

(0,1) | t1

(0,2) | t2

postgres=# update test set value = 't2n' where value = 't2';

UPDATE 1

postgres=# select ctid, value from test;

ctid | value

-------+-------

(0,1) | t1

(0,3) | t2n

The updated row didn’t stay at offset 2. Postgres deleted the old tuple and inserted a new one at offset 3. This is MVCC - Multi-Version Concurrency Control. The old version is kept around so that other transactions that started before the update can still see the original data. Postgres tracks this with xmin and xmax transaction IDs:

postgres=# SELECT lp as tuple, t_xmin, t_xmax, t_ctid

FROM heap_page_items(get_raw_page('test', 0));

tuple | t_xmin | t_xmax | t_ctid

-------+--------+--------+--------

1 | 907 | 912 | (0,3)

2 | 910 | 911 | (0,2)

3 | 912 | 0 | (0,3)

Dead tuples stay in the page until VACUUM cleans them up.

This matters because it explains why a table with 4000 updates per minute has its rows scattered all over the place. Every update creates a new tuple somewhere in the table. Over time, rows that logically belong together (same account_id) end up physically spread across thousands of pages. And when Postgres follows an index to fetch those rows, each one can be in a completely different page - meaning a completely different disk read.