How does the Kernel handle TCP requests?

My first encounter with sockets changed everything. It was one of those “aha!” moments where the internet’s machinery suddenly clicked into place. The internet is a beautiful, beautiful thing. There are so many things to say about how it works - from application protocols, such as HTTP - to sharks biting internet cables in the ocean.

I often ask myself: how the hell did they invent something so cool as communication between processes running on different and distant machines? The design is actually tremendously simple. Let’s find out.

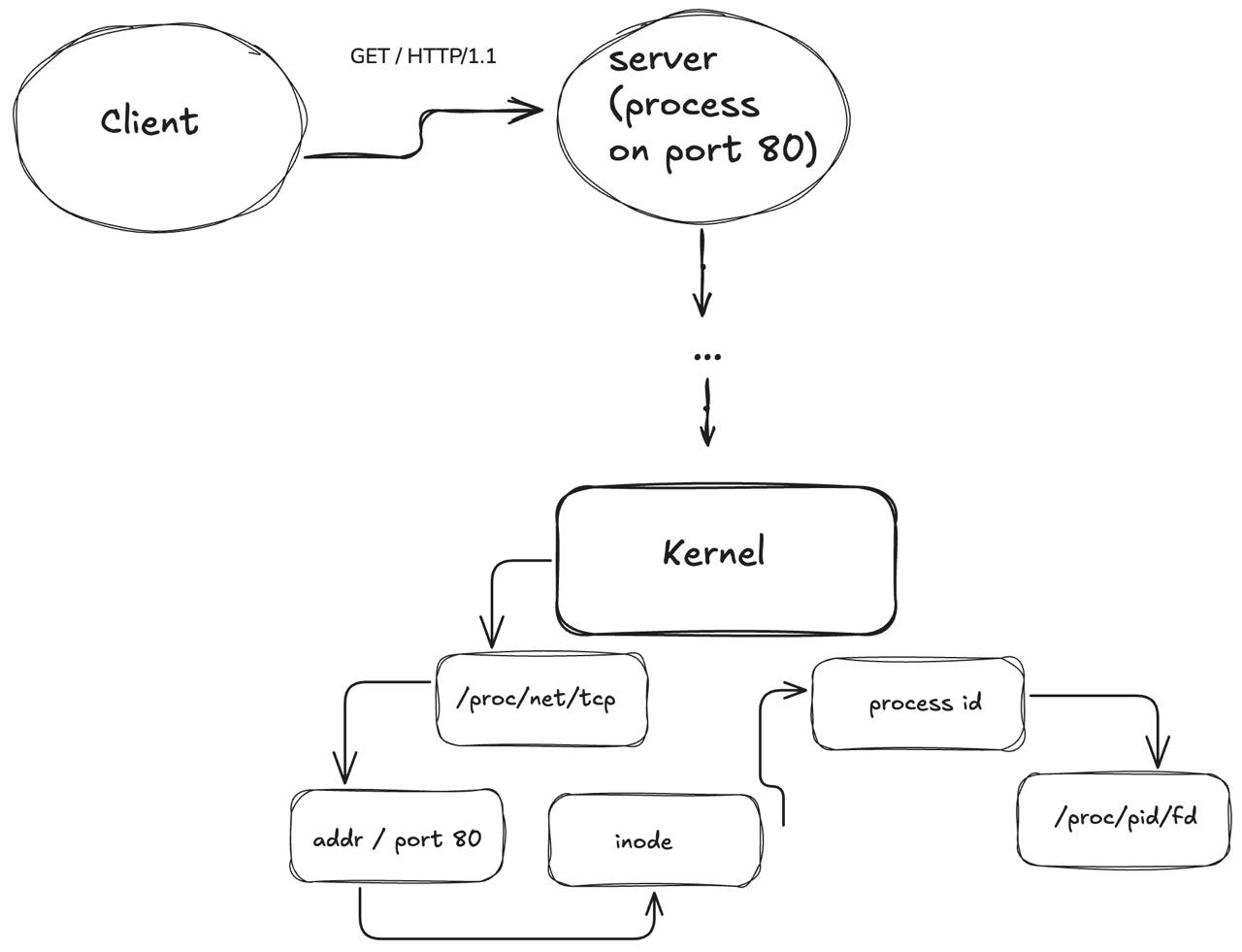

When a request is received by the machine, the Kernel asks itself: “Hey, do I have a socket file descriptor opened on port 80? Let me check”. Then it checks a special table for internet connections: a socket table. We can actually see what’s going on there:

cat /proc/net/tcp

➜ ~ cat /proc/net/tcp

sl local_address rem_address st tx_queue rx_queue tr tm->when retrnsmt uid timeout inode

4: DE01A8C0:0016 7401A8C0:DE24 01 00000000:00000000 02:0006FC06 00000000 0 0 1030697 2 0000000062dd485f 20 4 31 7 7

5: DE01A8C0:0016 7401A8C0:DE21 01 00000000:00000000 02:0006F94E 00000000 0 0 1030660 2 000000005ddb2235 20 7 31 9 7

We don’t need to specify the process ID in /proc/net/tcp because whether we specify it or not the output will be the same: a list of all tcp connections available in that namespace. It contains both listening and connected sockets, and gives us reference to remote and local addresses (local_address and rem_address).

After the kernel checks the socket table, it has access to the file descriptor table, in which it tries to find which process that socket is running on. But how does it find the process by identifying the socket? Well, the last information in /proc/net/tcp is the inode number. The kernel then finds the process in /proc/pid/fd.

Are you curious about this? Open a terminal and run a server:

checking out /proc stuff

➜ ~ python -m http.server 8080

Serving HTTP on 0.0.0.0 port 8080 (http://0.0.0.0:8080/) ...

On another terminal, find the ID of the process that is running the server:

➜ ~ ps aux | grep "python -m http.server 8080" | grep -v grep

frns 168674 0.2 0.0 27752 19644 pts/1 S+ 23:58 0:00 python -m http.server 8080

Now we can see what file descriptors this process has!

➜ ~ ls -l /proc/168674/fd

total 0

lrwx------ 1 frns frns 64 Jan 1 23:59 0 -> /dev/pts/1

lrwx------ 1 frns frns 64 Jan 1 23:59 1 -> /dev/pts/1

lrwx------ 1 frns frns 64 Jan 1 23:59 2 -> /dev/pts/1

lrwx------ 1 frns frns 64 Jan 1 23:59 3 -> 'socket:[1200452]'

Let’s grep /proc/net/tcp to check the correspondence:

➜ ~ sudo cat /proc/net/tcp | grep 1200452

2: 00000000:1F90 (...) 200452 1 0000000002730145 100 0 0 10 0

This could be magic! Hm. But it must be complicated to run a socket by hand, right?

running a tcp socket

It’s not complicated at all. Let’s use Python to do this, since Python’s socket interface is similar to TCP socket standard.

First we create a new socket, bind it to an address and port, and start listening to it.

import socket

s = socket.socket(socket.AF_INET, socket.SOCK_STREAM)

s.bind(('localhost', 8080))

s.listen(1)

Then we loop, like all things computer. We call accept to get the connection, and then recv to receive bytes. Let’s find out how this works:

while True:

conn, addr = s.accept()

print(f"Connected by {addr}")

while True:

data = conn.recv(1024)

if not data:

break

print(f"Received: {data.decode()}")

conn.send(b"Got your message\n")

conn.close()

First, let’s run the process and find out its ID.

➜ ~ python tcp_socket.py

➜ ~ ps aux | grep "python tcp_socket.py" | grep -v grep

frns 172143 0.0 0.0 15704 10264 pts/1 S+ 00:37 0:00 python tcp_socket.py

Then we strace it:

➜ ~ sudo strace -p 172143

strace: Process 172143 attached

accept4(3,

accept4(2) “(…) extracts the first connection request on the queue of pending connections for the listening socket, sockfd, creates a new connected socket, and returns a new file descriptor referring to that socket. The newly created socket is not in the listening state. The original socket sockfd is unaffected by this call”[^1].

by this point (without even send a single request!) we already have two sockets on this process! The first socket was created for the handshake. By the time our process called accept4, a new socket was created and returned to the process. What happened is something like this:

Process: socket() → One listening socket created

Process: bind() + listen() → Socket starts accepting connections

Client: SYN →

Server: ← SYN-ACK All using the same listening socket

Client: ACK →

Process: accept4() → NOW kernel creates second socket

Now let’s create a sending socket with netcat:

➜ ~ nc localhost 8080

By this point, our server called two syscalls: 1. getsockname(2) is the system call responsible for returning the current address to which the socket is bounded (in this case, 127.0.0.1:8080). 2. recvfrom(2) is used to receive messages. In our case, we specified that our receiving buffer has 1024 bytes (recv(1024)). This matters because only 1024 will be send at a time.

Let’s send something to our server using the netcat terminal:

➜ ~ nc localhost 8080

Hello from netcat!

We immediately get the response:

Got your message

By this point the process called recvfrom with out message, and then sendto with the response body: Got your message\n. After this, the server is “stuck” in the recvfrom again, waiting for a new request to be processed.

What happens if we send a request with more than 1024 bytes? I will copy some Hamlet to the netcat terminal.

The first scene alone was enough for 56 Got your message responses. Nice!

closing the socket

By the end of our program, we call conn.close(). This calls close(2) syscall, which is responsible for cleaning up everything related to file descriptors. Let’s see what man page has to tell us:

The close() call deletes a descriptor from the per-process object reference table.

Phew. I guess this is it. Can we appreciate webservers now?